- ShreeHistory

- History

- Hits: 99

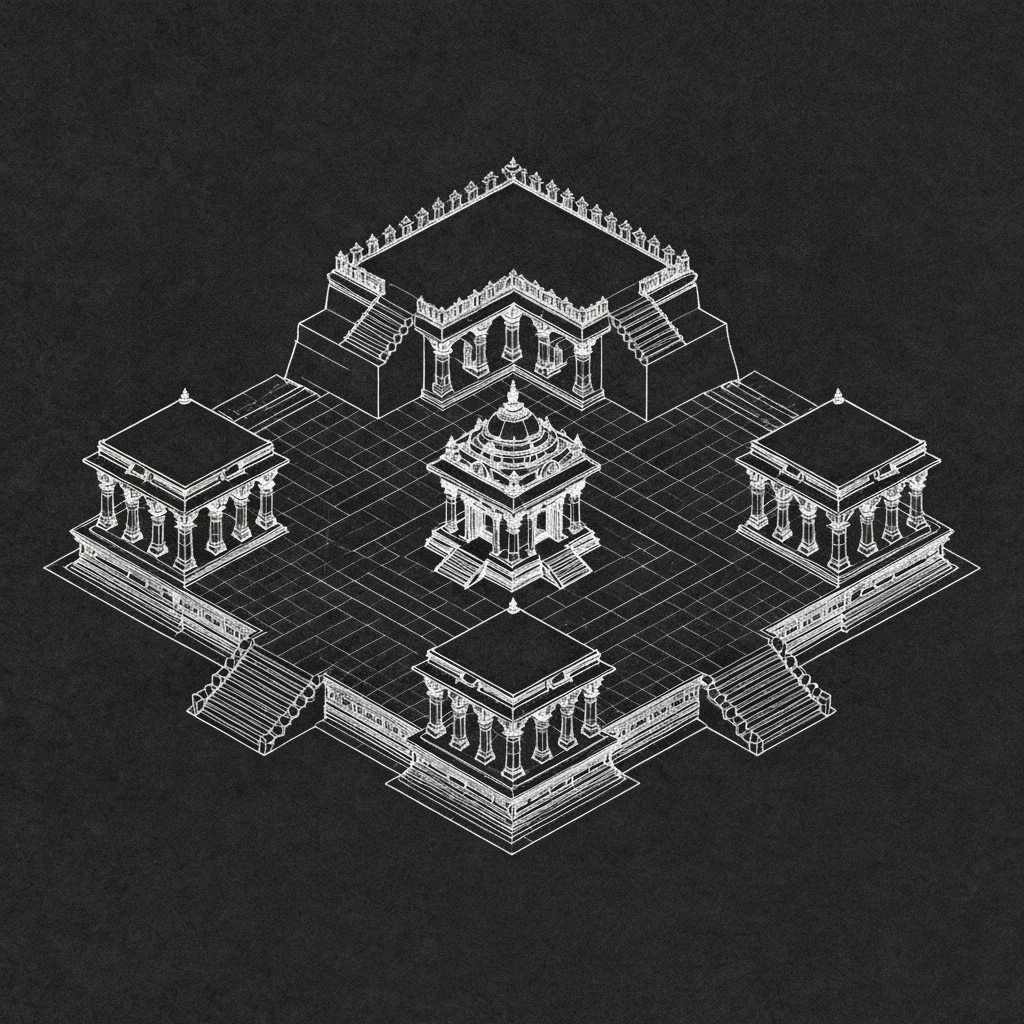

Sarvatobhadra Temple Architecture

Sarvatobhadra Temple Architecture:

The Indigenous Foundation of Humayun's Tomb and the Taj Mahal

The Sarvatobhadra temple represents one of the most sophisticated planning systems in ancient Hindu architecture, and its principles became the fundamental blueprint for major monuments built during the Mughal period in India, particularly Humayun's Tomb and the Taj Mahal. This architectural connection reveals the deep indigenous roots underlying structures commonly attributed solely to Islamic architectural traditions

The Sarvatobhadra Temple System

The Sarvatobhadra temple, described in detail in the Vishnudharmottara Purana (an ancient Hindu text on architecture), belonged to the eighth classification of Hindu sacred structures. The name derives from sarvata (from every side) and bhadra (auspicious), indicating a temple characterized by auspiciousness and accessibility from all directions.

Key Architectural Features

The Sarvatobhadra temple exhibits distinctive elements that make it unique among Hindu architectural forms:

1. Elevated Square Platform (Jagati)

The temple rests on a broad, square terrace called jagati—a raised platform that serves multiple purposes including circumambulation (pradakshina) and establishing sacred space. This elevation creates both practical and symbolic separation from the mundane world.

2. Central Sanctum (Garbha-griha)

At the heart of the plan sits the square garbha-griha (literally "womb-house"), the innermost sanctum housing the primary deity. This represents the cosmic center, the axis mundi connecting heaven and earth.

3. Four Mandapas in Cardinal Directions

Surrounding the central sanctum are four mandapas (pavilions or halls) extending in the four cardinal directions—north, south, east, and west. This creates a cruciform or cross-shaped plan radiating from the center.

4. Four Corner Chambers (Prasadas)

Between the four mandapas, in the diagonal corners, sit four smaller chambers or subsidiary shrines (prasadas). This arrangement creates what R. Nath describes as an "octagonalized-square plan" when the corners are chamfered.

5. Four-Way Accessibility

The Sarvatobhadra features entrances at all four cardinal points, allowing approach from any direction. Staircases on each of the four sides of the platform provide access.

6. Enclosing Rampart (Prakara)

A surrounding wall or prakara defines the sacred precinct, with subsidiary shrines (devakadis) positioned at the corners of the terrace.

7. Sacred Water Features

Integrated into the design are beautiful tanks and water channels arranged around the central shrine on the terrace, serving both ritual and aesthetic purposes.

8. Panch-Ratna Symbolism

The temple embodied the panch-ratna (five-jewel) formula: one central shikhara (tower) over the garbha-griha and four subsidiary shikharas over the four mandapas, creating a cluster of five towers with the central one dominating.

Textual Authority

Multiple ancient Hindu architectural texts describe the Sarvatobhadra:

-

Vishnudharmottara Purana provides the most elaborate description in its 87th chapter of the third part, devoting an entire chapter to this unique temple type

-

Matsya Purana (Chapter 269) specifies that Sarvatobhadra temples should bear many shikharas

-

Brhat-Samhita prescribes four doors, many domes, many beautiful chandrashala (moon-shaped arch forms), five storeys, and a breadth of twenty-six cubits

-

Visvakarmaprakasha and Samarangana-Sutradhar also document this temple form with variations in measurements and proportions

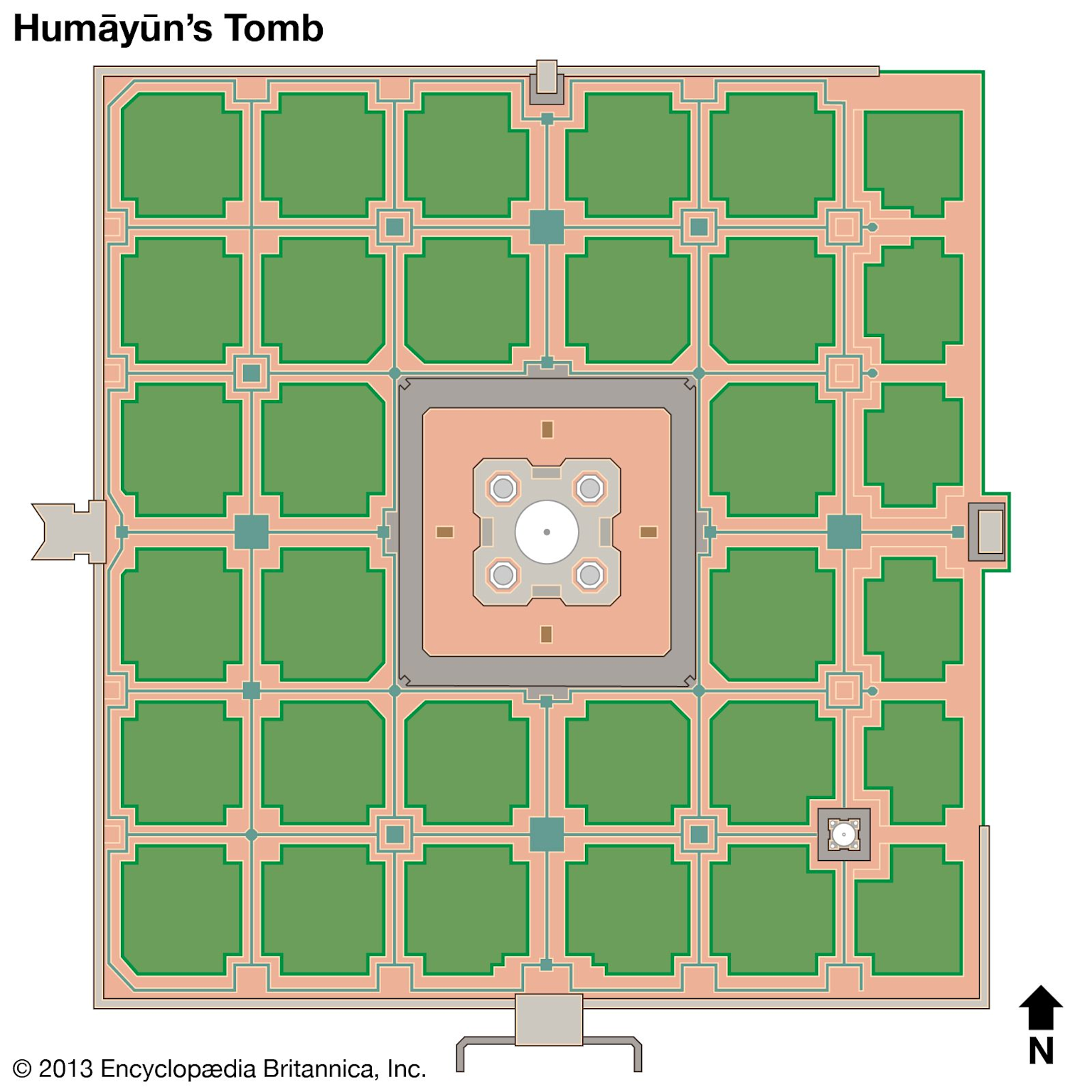

Humayun's Tomb: The Sarvatobhadra Plan Materialized

When Humayun's Tomb was constructed between 1564-1570 in Delhi, the structural correspondence to the ancient Sarvatobhadra temple plan became unmistakable. R. Nath, in his doctoral dissertation "The Immortal Taj Mahal," makes this connection explicit.

Direct Architectural Correspondences

Plan Configuration: The Octagonalized Square

The tomb sits on a raised plinth 22 feet (6.71 meters) high, directly paralleling the elevated jagati of Hindu temples. The main structure follows a square plan measuring 156 feet (47.54 meters) per side, with its angles chamfered (cut at an angle), thus creating an octagonalized square—precisely the Sarvatobhadra configuration.

R. Nath explicitly states: "This description fundamentally corresponds to the plan of the tomb of Humayun and as there is no such prototype traceable in Persia or any other Islamic country". This unequivocal scholarly acknowledgment establishes that the planning system derives from indigenous Hindu architectural traditions, not from Persian or Islamic sources.

Interior Arrangement: Garbha-griha and Surrounding Chambers

The interior spatial organization replicates the Sarvatobhadra system with remarkable precision:

-

Central octagonal chamber: Functions as the garbha-griha, the focal point of the entire structure

-

Four octagonal corner chambers: Correspond to the four corner prasadas of the temple plan

-

Four side rooms: Represent the four cardinal mandapas

-

Interconnecting passages: All spaces connect through corridors, creating the circumambulatory (pradakshina) path characteristic of Hindu temples

R. Nath further identifies this arrangement with the Hemakuta temple system, which featured an Andhakarika (dark ambulatory)—a circumambulatory passage surrounding the central garbha-griha, enclosed within outer walls. He concludes: "This was known to the Indian builder and so the interior plan of the tomb probably owes its origin to him rather than to Mirak Mirza Ghiyas or any other Islamic builder".

Four-Way Accessibility: Cardinal Direction Gateways

Like the Sarvatobhadra temple, Humayun's tomb complex has gateways in all four cardinal directions. The main entrance on the west corresponds to Hindu temple orientation principles, which sometimes place primary entrances facing west for Shiva temples, as prescribed in the Shulba Sutras.

Each gateway provides axial approach to the central tomb, maintaining the four-fold symmetry inherent in the Sarvatobhadra concept. The pathways from each gateway lead directly to the central structure, preserving the Hindu principle of approaching the sacred center from multiple auspicious directions.

Water Features: Sacred Hydraulics

Small tanks and water channels integrate into the platform design, paralleling the sacred water features prescribed for Sarvatobhadra temples. The hydraulic system includes:

-

Overhead tanks ensuring water pressure

-

Underground earthen pipes feeding fountains

-

Channels (chadars) with flowing water

-

Lily ponds at intervals

-

Fountains marking cardinal and intercardinal points

This sophisticated water engineering reflects Hindu understanding of sacred hydraulics, where water represents purification, prosperity, and the flow of cosmic energy.

The Char-Bagh: Islamic Overlay on Hindu Plan

While Babur introduced the Persian char-bagh (four-part garden) concept to India, providing the landscape setting, the architectural plan of the tomb structure itself derives entirely from the Hindu Sarvatobhadra system.

R. Nath clarifies: "The square plan of the main structure, approachable from all the four sides, was however known to the Indian builder since ancient times". The indigenous architect adapted the ancient Sarvatobhadra plan to the new context of tomb construction, demonstrating continuity of Hindu architectural knowledge systems.

The char-bagh garden, divided into four quadrants by water channels, actually resonates with Hindu cosmological concepts of four-part spatial division found in vastu purusha mandala (the sacred geometric diagram underlying Hindu architecture). The four cardinal directions hold deep significance in Hindu thought, corresponding to directional deities (dik-palakas) and cosmic ordering principles.